Alayna Cole

Alayna Cole is an MCA (Creative Writing) candidate who loves to write stories when she’s not studying.

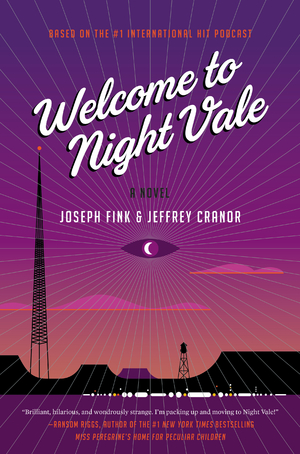

Welcome to Night Vale is a novel based on the incredibly popular podcast of the same name. The podcast is a way for non-residents of the fictional desert community to listen to broadcasts from the Night Vale Community Radio station—a staple in Night Vale households whether they like it or not—as Cecil tells us about the many mysteries that plague the peculiar town.

Welcome to Night Vale is a novel based on the incredibly popular podcast of the same name. The podcast is a way for non-residents of the fictional desert community to listen to broadcasts from the Night Vale Community Radio station—a staple in Night Vale households whether they like it or not—as Cecil tells us about the many mysteries that plague the peculiar town.

The novel adaptation of the podcast primarily follows two specific mysteries (while often deviating onto other strange, tangential narrative paths) and contains all of the bizarre absurdities that lovers of the podcast have come to expect. But that’s not to say you need to be a long-time listener of the Welcome to Night Vale podcast to enjoy this book. While those already familiar with the Night Vale community may notice the occasional reference before somebody who is new to this universe, every peculiarity is introduced in a way that provides enough context for all readers to interpret—if not understand—what is going on.

And not quite understanding is part of the joy of Night Vale.

In this way, I’m sure Welcome to Night Vale is a ‘love it or hate it’ experience. Some people will dislike the unusual narrative style, with a narrator who insists that you imagine something—a teenage boy, for instance—and then tells you that you’re imagining it wrong. The narrative is often derailed by seemingly-irrelevant transcripts of Cecil discussing the traffic or reminding us that librarians are dangerous. Anybody who prefers a narrator who tells a nice, linear story while minding their own business and staying inside their book likely won’t enjoy their adventure through Night Vale.

I only needed to read the foreword of Welcome to Night Vale to know that this novel would quickly become one of my favourites. The book is incredibly clever. Details are revealed and withheld with deliberation and care, leaving the reader with a haunting, lingering mental image of a town that is dissonant when compared to their own, but that is also terrifyingly similar.

I remember being introduced to the principle of ‘Chekhov’s gun’ in a first year creative writing subject at university, and Welcome to Night Vale is the embodiment of that idea. If you’re unfamiliar, this principle suggests that everything included in a story must be relevant to that story, or else should be removed. Even the smallest reference to the strangest thing in Welcome to Night Vale comes up again at one time or another, and the most surprising characters and objects become integral to the overall story. In this way, everything that happens in Night Vale is linked to everything else that happens in Night Vale. Time and space are weird, dude.

As I worked my way through the novel, I encountered innumerable sentences that were so interesting or bizarre that I just wanted to read them aloud to someone. I involuntarily became the annoying person who sits next to you at a movie and points out all the clever parts, but without the benefit of you having any knowledge of the surrounding story. I was so excited by this ridiculous adventure that I just had to share it with the people around me.

I enjoyed being told to imagine things. I even enjoyed being told that the things I was imagining were wrong and that I should try again. I liked being given incredible detail about some of the characters, objects, or settings, but almost none about others. Welcome to Night Vale made me think, made me ask questions, and made me marvel and wonder at the world I was travelling through as well as my own.

At first glance, Welcome to Night Vale seems to be completely distant from the places we inhabit. After all, we don’t have teenage boys who can morph into whatever physical form they want, or a pawn shop where we have to perform strange hand-washing rituals before we can pawn our items, or doors that need to be shouted at before they will open. And yet the residents of Night Vale consider these goings-on entirely normal—or, at least, mostly acceptable.

However, on closer inspection, perhaps there are aspects of our lives that we accept, but that would seem just as unusual to an outsider, looking in. Our teenagers may not be able to transform themselves from human form into that of a wolf-spider or a sentient haze at will, but they are asking similar questions about who they are, how they should look, and how to fit in. We may not need to wash our hands while chanting in order to pawn our possessions, but we have many strange rituals and routines of our own. Often Welcome to Night Vale touches on realities that are a little too relatable, like the strange thoughts many of us seem to miraculously have while in the shower, or the distress that sometimes comes when inhabiting the space between waking and dreaming.

Welcome to Night Vale spends a lot of time exploring the lives of the community’s many and varied characters. Some have flaws, most have peculiarities, and all are relatable in one way or another. While the development of the two female protagonists is evident, many of the side-characters seem to progress very little, acting as symbols for greater issues or signposts for the narrative while lacking their own fully-fledged personalities. But in a lot of ways, that’s the point. Characters struggle to understand the routines they find themselves trapped in, to decide whether they enjoy what they do every day, and to remember how they even came to be where they are. In doing so, these side-characters cause the protagonists—and the reader—to ask themselves: am I a fully-fledged character? Do I know how I came to be where I am? Do I like it here?

Welcome to Night Vale is a wonderful journey into absurdity that will make you ask a lot of questions. At first, you will be wondering ‘What are those strange lights in the desert?’ and ‘How can a house be sentient?’ but before long—before you even notice the questions have changed—you will be asking different things, like ‘Who am I?’ and ‘What am I doing with my life?’

All hail the Glow Cloud.

Apologies for the downtime in November; I was on a month’s holiday in North America. My intentions of keeping up regular posts proved more difficult than I expected. Anyway, I’ll be popping back next week with my 2015 reflections, but in the mean time, just wanted to say thank you to those who read this blog and support my writers and myself in our craft. You have my gratitude and much applause.

Apologies for the downtime in November; I was on a month’s holiday in North America. My intentions of keeping up regular posts proved more difficult than I expected. Anyway, I’ll be popping back next week with my 2015 reflections, but in the mean time, just wanted to say thank you to those who read this blog and support my writers and myself in our craft. You have my gratitude and much applause.