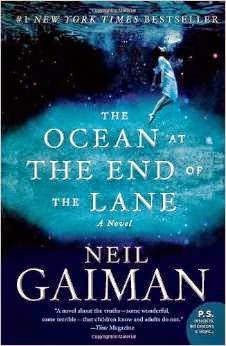

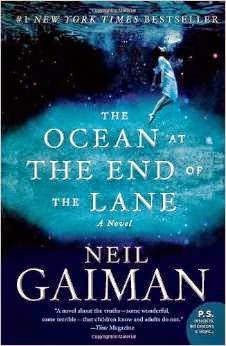

Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a masterful work of speculative fiction, which recollects an unnamed narrator’s childhood, which he is reminded of upon visiting a property known as the Hempstock Farm.

Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a masterful work of speculative fiction, which recollects an unnamed narrator’s childhood, which he is reminded of upon visiting a property known as the Hempstock Farm.

The novel relies on a framing narrative where the narrator is driving around the town where he grew up. He is inexplicably drawn to the property where his childhood home once stood, and then further along the lane to the Hempstock Farm and the pond that his friend Lettie had referred to as ‘her ocean’.

Framing narratives that surround a recollection generally work to instil confidence in the reader that the characters will remain safe from harm within those memories. However, Gaiman manages to destabilise this belief as events unfold, successfully creating discomfort and mystery for the audience. This destabilisation is increased by the unreliability of the narrator.

There are several factors contributing to the unreliability of this text’s unnamed narrator. Firstly, the fact that he isn’t given a name works to distance him from the reader and makes it more difficult to trust his narrative. Anonymity can sometimes give a person the freedom to be honest without judgement, but can also cause a person to lack the accountability required for them to tell the whole truth. This uncertainty is combined with the idea that many decades have passed between the narration and the narrated, and the impact of time can cause memories to shift and change. The story is told predominantly from the perspective of a child, and the memories of a child are often skewed by a misconception of time and space. The narration is made more unreliable still through the recurring theme of memory; it is highlighted that different people remember situations differently, and the inference that the Hempstocks have the power to change and manipulate time to suit themselves makes it difficult to determine what actually happened and what has been altered. The unnamed narrator has duplicate memories of some events, so it’s impossible to determine which are the ‘true’ events and which were changed, or didn’t happen at all.

The contrast between adult and child in this text is apparent through the shift of time and also through language use. Characterisation is achieved through the language utilised within the narration and dialogue. The Hempstock family has a slightly different dialect than the unnamed narrator and his family, and this is different again to the language used by Ursula, the opal miner, and other secondary characters. This highlights the age difference between characters, as well as their differing social contexts. It also works to separate the unnamed narrator in the framing narrative to him as a child in the recollections, while showing similarities between the Hempstock woman that he meets at the farm and those in his memories, adding to the mystery of who the Hempstocks are and how long they have been at Hempstock Farm.

Mystery is an important element in this text and is introduced through the strange, unexplained and magical themes. More importantly however, the mystery is continued through the questions that remain half-answered or entirely unanswered, even after the novel is finished. Throughout the book, it’s accepted that certain areas and people have magical properties or inexplicable traits, and the importance of these elements is described without their origins being explicitly stated for the reader. In this novel, Gaiman refuses to hold the reader’s hand, revealing the idea of different worlds, immortality and a magical ocean without truly explaining how or why these things exist, or if they were really any more than the fantasies of a child with a passion for reading about and creating stories.

The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a magical tale, with setting descriptions and characters that transport the reader to the lane where the unnamed narrator and the Hempstocks once lived. But its these mysteries and unanswered questions that truly cause this narrative to linger with the audience and encourage a second read-through.

So what have I been up to this past while?

So what have I been up to this past while?

Well, yes it was fun! S’plosions, one liners, music (Cherry Bomb!), abs a-plenty, Groot (‘we are all groot!’ sob!), some good old fashioned heroics, and Rocket the smart-mouthed raccoon.

Well, yes it was fun! S’plosions, one liners, music (Cherry Bomb!), abs a-plenty, Groot (‘we are all groot!’ sob!), some good old fashioned heroics, and Rocket the smart-mouthed raccoon. Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a masterful work of speculative fiction, which recollects an unnamed narrator’s childhood, which he is reminded of upon visiting a property known as the Hempstock Farm.

Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a masterful work of speculative fiction, which recollects an unnamed narrator’s childhood, which he is reminded of upon visiting a property known as the Hempstock Farm.