A. C. Grayling, continuing to develop the persona of the public intellectual, has produced a mature set of essays for any person with an interest in the world around them as perceived through the prism of applied philosophy and a discerning mind.

A. C. Grayling, continuing to develop the persona of the public intellectual, has produced a mature set of essays for any person with an interest in the world around them as perceived through the prism of applied philosophy and a discerning mind.

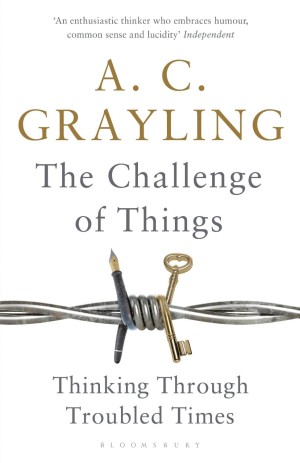

Grayling is known as a highly accomplished British philosopher, boasting a PHD from Oxford University and a publishing history consisting of over 30 books. His latest book, titled “The Challenge of Things: Thinking Through Troubled Times” is Grayling’s continuing mission to contribute to, and stimulate, intellectual debate on a myriad of issues.

The book is sectioned into “Destructions and Deconstructions” and “Constructions and Creations”, which can be roughly translated into an evil-good divide (in the optimistic form of leaving the best to last). These sections are then further broken down into essays covering a broad and fascinating scope. The essays are derived from Grayling’s recently published works as well as new material composed specifically for the book.

Although none of the essays are sufficiently long to thoroughly account for a given topic, Grayling masterfully sows the seeds of his own opinions while directing inquiring minds in the right direction. Grayling is at his best when argumentative and his writing shines in the spirited defence of ideas such as secularism of the state, gun laws, freedom of speech and the inestimable value of friendship. His comprehensive grasp of historical, sociological, scientific and, of course, philosophical concepts provides a tremendous depth to his insights and conclusions. However, perhaps the most enjoyable aspect of the book is the iridescent humanism which infuses each essay: a sense of hope and, ultimately, trust in the nature of humanity, provided we have recourse to our rational faculties.

The less compelling essays in the book tend to see Grayling meandering on historical topics, which appear to be of personal interest with fairly weak and ancillary links to contemporary life. Grayling is also guilty of the occasional descent into intellectual condescension when dealing with authors or schools of thought of which he is not particularly enamoured. Despite this, most of the essays are not longer than three or four pages so it is very easy to read ‘just one more’ and chances are it will be worth it.

This book is highly recommended for any person seeking to sharpen their thinking on modern ethical and philosophical questions while being propelled along by an accomplished and discerning writer.