In Praise of Fantasy

For many long years readers of fantasy have happily ignored the way the larger world sneers at their genre. Even writers within the genre of speculative fiction have been critical of the subgenre, fantasy. In his iRoSF article ‘Peter Jackson and the Denial of the Hero,’ M. Garcia quotes China Mieville on epic fantasy:

For many long years readers of fantasy have happily ignored the way the larger world sneers at their genre. Even writers within the genre of speculative fiction have been critical of the subgenre, fantasy. In his iRoSF article ‘Peter Jackson and the Denial of the Hero,’ M. Garcia quotes China Mieville on epic fantasy:

‘Tolkien is the wen on the arse of fantasy literature. His oeuvre is massive and contagious—you can’t ignore it, so don’t even try. The best you can do is consciously try to lance the boil. And there’s a lot to dislike—his cod-Wagnerian pomposity, his boys-own-adventure glorying in war, his small-minded and reactionary love for hierarchical status-quo’s, his belief in absolute morality that blurs moral and political complexity. …. He wrote that the function of fantasy was ‘consolation’, thereby making it an article of policy that a fantasy writer should mollycoddle the reader (Miéville, PanMacmillan).’

But not everything Mieville has to say about Tolkien is derogatory. In his Socialist Review article, ‘Tolkien’s Middle Earth and Middle England’, he says:

‘Tolkien’s most important contribution by far, and what is at the heart of the real revolution he effected in literature, was his construction of a systematic secondary world. There had been plenty of invented worlds in fantasy before, but they were vague and ad hoc, defined moment to moment by the needs of the story. Tolkien reversed that. He started with the world, plotted it obsessively, delineating its history, geography and mythology before writing the stories. He introduced an extraordinary element of rigour to the genre.’

It was this depth of world building that made readers buy into Middle Earth and it was the promise of adventure based on wondrous myths that kept them reading. In a post for the Australian Literature Review on Fantasy: Why is the genre so popular? I argue that:

‘Whether these (fantasy) stories are set in our world or a secondary world where magical creatures and/or people exist, they all share a common theme: the exploration of the human condition. Even the much maligned medieval/quest fantasies offer their readers the chance to vicariously explore a wondrous world, battle evil and restore justice. Even a lowly Hobbit can change the course of the world by destroying the Ring.

That is the appeal of the tolkienesque fantasy. In our modern world where politicians prove corrupt, large corporations rip off consumers and terrorists kill ordinary people going about their daily lives, the traditional quest fantasy provides an antidote to cynicism. Fantasy, deriving from the word fantastic, exercises our sense of wonder.’

That is the appeal of the tolkienesque fantasy. In our modern world where politicians prove corrupt, large corporations rip off consumers and terrorists kill ordinary people going about their daily lives, the traditional quest fantasy provides an antidote to cynicism. Fantasy, deriving from the word fantastic, exercises our sense of wonder.’

Could there be a back-swing seeking to recognise the power of fantasy? Recently Louise Schwartzkoff wrote a piece for the Sydney Morning Herald titled ‘A sucker for a fantastic story’. She brings up the conundrum many fantasy readers come across when they do a BA in Literature. Some of the books they read are fantasy or science fiction, but the authors brand themselves as literature. She says:

‘Margaret Atwood’s perturbing The Year of the Flood was sold in Australia with a black cover choked with thorny vines. Atwood says the book is not science fiction at all, preferring the more reputable label ‘speculative fiction’. Looking at the storyline – a genetically engineered virus all but wipes out humanity – it is hard to see this as anything but an attempt to protect the book from ‘literary snobbery.’

Similarly, in his article, ‘The fantastic appeal of fantasy’, on the subject of literary snobbism Mark Chadbourn quotes Jo Fletcher, editorial director of fantasy publisher Victor Gollancz.

“For years I have been asking why one of the greatest satirists who ever lived – in this country or any other – is consistently ignored by those who ought to be lionising him. I’m talking about Terry Pratchett, who may have the financial rewards commensurate with his talent – but where are the Booker prizes, or the Whitbreads ? Where are the literary accolades? Whenever he’s interviewed, it’s usually with a faint air of surprise that someone who writes fantasy can be so erudite and funny.”’

Chadbourn goes on to say:

‘Publishers love the genre because it reaches all people – highbrow readers attracted to the skilful writing of M. John Harrison, say, or those simply wanting a well-told adventure story by the best-selling Robert Jordan, men and women in equal measure, young and old.

Received knowledge among non-readers suggests fantasy is simply a case of swords and sorcery or elves and dwarfs. Yes, there is that by the shelf. But the genre really is as broad as the imagination. It contains events on this world and any other world, on this side of life and beyond it. ‘

Four times World Fantasy Award winner, Margo Lanagan brings up the same point in her post The Appeal of Fantasy – Sparklies and Magic’. She says: ‘I don’t think fantasy stories are any less truthful or complex than naturalistic fiction, or even some forms of non-fiction. What you believe about the world will insist on bubbling up through your confections.’

You can explore discrimination and persecution within the fantasy genre because it frees readers from preconceived prejudices by removing loaded nouns such as Black and Jew, and substituting created nouns for created races.

In her Film Reference article on ‘Fantasy films – Theory and Ideology’ Katherine A Fowkes says.

‘By raising questions about reality and by revealing repressed dreams or wishes, fantasy makes explicit what society rejects or refuses to acknowledge. Indeed, to the extent that it includes the surreal and experimental, fantasy is often explicitly subversive. ‘

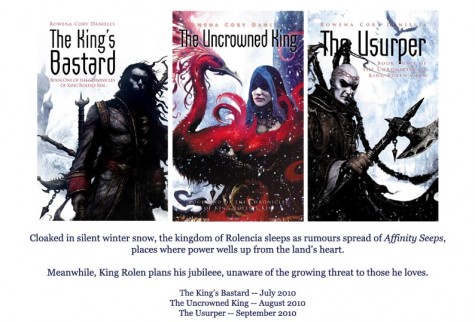

The fantasy genre is freeing. Sure it can deliver a rollicking read, which is what I set out to do with the King Rolen’s Kin trilogy. But I was also exploring discrimination and narrow mindedness. In his post ‘Counting Down My 11 Favourite Books of 2010’ Rob

Will Review discusses the trilogy these themes in the trilogy. He says:

‘ … people came to think that men who love men were indistinguishable from the conspiracy of men hellbent on overthrowing the king. The hatred of gay people and people with Affinity became similarly conflated.

Daniells uses this ingenious conceit to demonstrate how easily people can shift from one hatred to another, collapsing all perceived enemies into a hazily defined external or internal threat. In another thematically related subplot, Rolen decides to attack one of the Utland territories, even though he doesn’t know precisely which one attacked his kingdom. One is as good as any other. This seems to be a reference to George W. Bush’s successful bid to satisfy an American desire for revenge against Afghanistan by attacking Iraq, as well as to the general concept of a scapegoat. Meanwhile, the concept of people with Affinity and/or homosexual desire needing to hide the truth in order to keep fighting for their king or protecting their country and/or loved ones acts as a fascinating parallel to America’s “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, which unfortunately continues to be in effect.’

So there you have it. The fantasy genre can work on several levels. It can deliver a rollicking read. It can deliver that sense of awe and wonder and it can also be quite subversive and in the work of the wonderful Terry Pratchett.

So that is why I write fantasy, because of the versatility of this wonderful genre.